- Home

- Thomas Taffy

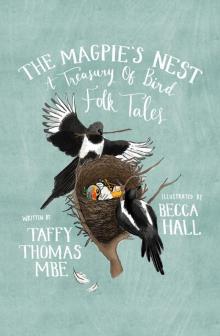

The Magpie's Nest

The Magpie's Nest Read online

First published 2019

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

Text © Taffy Thomas MBE, 2019

Illustrations © Becca Hall, 2019

The right of Taffy Thomas MBE to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9180 3

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

This book is dedicated to my father, Ivor Thomas, who still enjoys watching the birds and who taught me all their names; thank you dad. It is also dedicated to the memory of my mother-in-law, Audrey, who loved watching birds at breakfast time through the dining room window.

PROLOGUE

I talk with the Sun said the Wren

As soon as he starts to shine

I talk with the Sun said the Wren

And the day is mine.

CONTENTS

About the author

About the illustrator

Acknowledgements

Foreword

Introduction

1. The Wren

The Wren, King of the Birds

Wren Song

2. The Cockerel

The Sun, the Moon and the Cockerel

Cock Crow

A Tale of Two Roosters

3. The Magpie

The Magpie’s Nest

The Magpie and the Fox

4. The Blackbird

Kevin and the Blackbird

5. The Crow

The Vain Crow and the Clever Crows

The Vain Crow

The Clever Crows

The Raven Messenger

6. The Nightingale

Hodge and the Nightingale

7. The Skylark

Mother Nature and the Skylark

8. When Birds Gather

Kingfishers

Rooks

Owls

Linnets

Pheasants

Goldfinches

Larks

Geese

9. The Robin

The Robin and the Wren

The Helpful Robin

The Compassionate Robin

10. The Heron

The Heron’s Stance

Jack and the Heron

The Heron and the Fox

11. The Swallow

Why the Swallow Has a Forked Tail

12. The Snipe

Mother Snipe’s Wisdom

13. The Curlew

St Beuno and the Curlew

14. The Cuckoo

The Crewkerne Cuckoo Penners

The Borrowdale Cuckoo

15. The Pigeon

The Brave Pigeon

16. The Swan

The Mute Swans of Grasmere

17. The Woodpecker

Why the Woodpecker Is Still Tapping

18. The Owl

Why the Owl Has a Heart-shaped Face

The Owl Was a Baker’s Daughter

Epilogue

Riddle Answers

Two Short Rhymes

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Taffy Thomas has been living in the Lake District for well over thirty years. He was the founder of the legendary 1970s folk theatre company Magic Lantern, which used shadow puppets and storytelling to illustrate folk tales. After surviving a major stroke in 1985 he used oral storytelling as speech therapy, which led him to find a new career working as a storyteller.

He set up the Storyteller’s Garden and the Northern Centre for Storytelling at Church Stile in Grasmere, Cumbria; he was asked to become patron of the Society for Storytelling and was awarded an MBE for Services to Storytelling and Charity in the Millennium honours list.

In January 2010 he was appointed the first UK Storyteller Laureate at The British Library. He was awarded the Gold Badge, highest honour of the English Folk Dance and Song Society, that same year.

At the 2013 British Awards for Storytelling Excellence (BASE) Taffy received the award for outstanding male storyteller and also the award for outstanding storytelling performance for his piece ‘Ancestral Voices’.

More recently he has become patron of ‘Open Storytellers’, a charity that works to enrich and empower the lives of people marginalised because of learning and communication difficulties; he is also the patron of the East Anglian Storytelling Festival.

Taffy continues to tell stories and lead workshops, passing on both his skills and his extensive repertoire. He is currently working on a new History Press book ‘Storytelling for Families’, to enable families to enjoy this precious art form together at home.

ABOUT THE ILLUSTRATOR

Becca Hall is a freelance illustrator, based in the Lake District. After finishing her illustration degree in 2014, receiving a First Class with Honours, and the Illustration Alumni award, Becca has been working on a variety of projects and books, such as this one!

‘I love to draw and paint by hand, and am a little obsessed with the theme of nature, which is why the Lake District is perfect for me. One of my chosen projects at university was the theme of birds, so you can only imagine my excitement when I was asked to illustrate this book!’

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

In spring 2018 when the birds in The Northumberland National Park were fledging, a new project fledged for this storyteller. The creative team at The Sill: National Landscape Discovery Centre decided to put together a weekend of activities to celebrate the bird life of their National Park. Asked if I had sufficient bird folktales in my repertoire, I worked with National Park Ecologist Gill Thompson and Northumbrian Piper Paul Knox to create a programme of tales and tunes of the birds. This took some research and much delving into my memory. As this performance was well received and the audiences wanted to take the stories home with them, we decided that, with a little more research, there was sufficient material for this book of bird folktales.

It took a reunion with Lakeland artist Becca Hall, who grew up listening to my folktales at her Lake District infant school, to breathe beauty into this collection. We share a love of birdlife and we hope this comes across in our work that follows.

Thanks to all who gave me tales, lyrics and riddles that feature in this collection. These include storytellers Duncan Williamson, Marion Leper and Daniel Morden, and songwriters Bill Caddick and Leon Rosselson. I would also like to thank the fellow writers who have all been a source of information and inspiration – authors Francesca Greenoak, Mark Cocker and Richard Mabey, Aesop and Bob Hartman; poets Samuel Taylor Coleridge, John Clare, Seamus Heaney and William Wordsworth; folklorists Katherine M. Briggs, Ruth Tongue, Joseph Jacobs, Bob Patten and Sophia Morrison.

All the team at The History Press deserve my gratitude for their continuing patience and support. Steven Gregg and my daughter Rosie helped battle with a computer that is almost as old as (and definitely more tired than) the author.

Lastly, none of my books or live performances would be possible without the support of my wife Chrissy: ‘I won’t go on, I can’t go on, I will go on!’ Thanks Love.

FOREWORD

The histories and mythol

ogies of the British Isles are bound together with birds. They permeate our stories and songs, appearing as messengers and harbingers, speaking our secrets, and being our secret other selves. Birds guard us as we sleep, wake our ghosts, herald the seasons. Pheasants and their ‘ownership’ took on great political class-based significance after the Napoleonic Wars when ordinary people were starving in the fields and turned to poaching, often with tragic and community-destroying results.

Birds sing to us and we have always replied to them, an endless conversation. To sit quietly and hear them in the woodlands in the Spring is one of life’s great pleasures. To hear ‘the lark in the Summer air’, the soft cooing of doves, to watch gliding water fowl – a world without our birds would be a sad and silent one.

I’ve been lucky enough to grow up listening to Taffy’s stories, and then to have the honour and pleasure of playing for him as I’ve grown older. Those who know him know he is an endless mine of magic, treasure and wonder. Those that don’t upon encountering him soon grow to love him as I and thousands of others do.

A few years ago Taffy and Chrissy asked me if I would play for Taffy’s brilliant retelling of The King of the Birds story. I know a few different versions of the St. Stephen’s Day wren song but wanted to gift them both with their own version, so I put this together from a few different places and wrote them their own tune. Here is a verse, with all my love and gratitude for the years of happiness listening to Taffy weave with words:

Mr Thomas, a worthy old man

He’s come on home and he’s brought us a wren

Brought us a wren love to sing us a tune

So we can be happy on Old Christmas Morn

Hello, hello, hello boys

Hello, hello, hello

I hope you enjoy this beautiful book and that your family will treasure it and our birds for generations to come.

Eliza Carthy MBE

2019

INTRODUCTION

As I peer out of my kitchen window in the Storyteller’s House in England’s Lake District, I delight in observing the rocky outcrop that stretches upwards from the back of my house to the fell side. One day I saw a small yellowish bird, defying gravity by running down this slab of stone. By its colour and behaviour it identified to me as a nuthatch, a bird rich in folklore and legend. Nuthatches have always interested storytellers and folklorists as they are cloaked in superstition. One of the few positive outcomes of global warming is that this tiny treasure can now live as far north as the borders.

Once upon a time a wise old blackbird positioned a nest two-thirds of the way up this rock, like the nuthatch, defying gravity. This site was chosen so that a large cat at ground level standing on tippy-toes couldn’t reach it, and so the neighbour’s inquisitive cat, peering over the top of the rock, couldn’t stretch down to it. Imagine my delight this spring when a pair of blackbirds arrived, mud and twigs in beak, and started to fettle this old habitation. A few days later, when the busy pair were off on a worm hunt or seeking more building material, I risked peeking into the nest. To my delight there was a clutch of five light blue eggs. The brown bird of the pair sat on them patiently for a week or so whilst her mate brought her food. Then, one morning, I observed five tiny beaks peeping over the edge of the nest. My storytelling performances took me away from home for several days. On my return, there was no sign of the baby birds or their parents. With no sign of injured or dead birds in the garden I must presume that the miracle of life had been accomplished. My family of blackbirds successfully fledged. I can only hope a pair will return next spring, indeed for many to come.

If, however, I want to remember my first interest in our feathered friends I have to go back to my boyhood in the 1950s in Somerset. One of my earliest memories is of sitting on the knees of my twin aunts, Peggy and Barbara, whilst they recited ‘Two little dicky birds sitting on a wall’. My parental home and the much visited homes of both sets of grandparents all had gardens. They grew a mixture of flowers, fruits, vegetables and occasionally weeds. All provided welcome landing strips for our feathered friends. As a family we encouraged the visits of these avian adventurers. I remember well threading peanuts in their shell on wool, to be suspended between the washing line post and the canes strategically placed for the growing of sweet peas.

The stone bird bath was kept full for the blue tits’ synchronised swimming routines and the bird table often bore a banquet of bread and pastry crumbs, although starlings and jackdaws were usually discouraged from visiting by an adult rushing from the kitchen with a loud ‘shoo’ and windmilling of arms. Blackbirds, robins, wrens and finches were welcomed and from quite a young age I knew to greet them with their familiar names, Jenny, Robin and Blackie. On holiday trips to the seaside we were less friendly with the gulls, who felt it their right to try and avail themselves of my bag of chips. On visits to my maternal grandfather’s farm he once told me that having my cousin John and I in his fields was far more effective than his scarecrow.

As well as learning to name common birds I absorbed a knowledge of their folklore, largely through superstitions. I learned to salute a magpie whilst enquiring about the welfare of his family and reciting his rhyme – One for Sorrow … etc. As an adult I have learned that the sighting of two robins together is a sign of good luck, although realistically I have worked out that this almost never happens due to the territorial nature of these birds.

Until adulthood, like many people, I didn’t have the scientific knowledge of the migratory journeys of the birds I love. Even up until the twentieth century some folk were mystified by the disappearance and reappearance of the cuckoo and the swallow – they believed the cuckoo spent the winter with the fairies in fairy forts only to re-emerge and nest in the spring. The swallow, on the other hand, was believed to spend winter under the ice of our lakes and rivers, only reappearing in spring when the ice melted.

It’s only scientific development, the ringing of birds and GPS that have revealed migratory flights to far continents, almost too distant for us mere humans to even conceive. Now that is a truly magical story. I can only hope that you find my collection of tales that follow just as enchanting.

Taffy Thomas, The Storyteller’s House, Ambleside 2018

1

THE WREN

The dove says, ‘Coo, coo

What shall I do?

I can scarce bring up two.’

‘Fie, Fie!’ Says the wren

‘I have got ten

And keep them all like gentlemen.’

(Anon.)

The Wren, King of the Birds

This tale is quite a chestnut, but like so many such traditional, well or partially remembered stories, never fails to please. In telling, I usually reference the nearest high landmark, for example, in Lancashire, Pendle Hill, in London, Primrose Hill, and so on. Helm Crag in Grasmere, with its rock outcrops known as the Lion, the Lamb and the Old Lady playing the piano, lends itself well to the tale, particularly as, at one time, a pair of golden eagles had their nest on High Street on the slopes of Helvellyn, less than 5 miles from Helm Crag as the eagle flies.

A fine variant of this story can be found on the Isle of Man and, to this day both there and in Ireland, you can find the tradition of the Wren Boys, singing and begging on the day after Christmas Day, St Stephen’s Day.

The wren, the wren, King of all birds

St Stephen’s Day was caught in the furze

Though he is small, his family is many

We pray you, good people to give us a penny.

It wasn’t in your time, it wasn’t in my time, but it was in somebody’s time, all the birds of the air gathered on top of a great mountain. The sky was black with birds.

They wanted to settle once and for all which of them was King. Perhaps it should be the cleverest or the most handsome. You can only imagine the crowing, the squawking and the scolding as each protested its superiority over the others.

The rook, the raven, the jackdaw and the crow shone black, others s

howed brighter plumage. On a rock, arrogantly believing himself to be above all of them, was the golden eagle; he couldn’t help boasting and posing.

On the signal from the owl, or as we say in Lakeland, the hullet, each bird took it in turn to tell of their abilities and their worth.

The goldfinch spread her bright feathers; forktail the swallow told of his swiftness and travels to far southern climes; the thrush opened her beak allowing her beautiful song to soar skyward and all who heard thought she must surely win; then the jackdaw and the magpie started squabbling about which was the best thief; little Jenny Wren hopped forward to show her worth, but no-one noticed as she seemed so small and insignificant. Indeed it was even as she was saying her piece:

Small though I am and slender my leg

Twelve chicks I can bring out of the egg

That the golden eagle pushed in front of her, loudly proclaiming that the best bird on the wing should be the one to be the king.

All agreed that this would be a good idea and, before anyone could challenge the decision, the hullet hooted and they all took to the air.

Of course, the golden eagle was out in front followed by the swallow, then the big black birds, the rook, the raven, the jackdaw and the crow. Then came the chattering magpies calling,

One for sorrow

Two for joy

Three for a girl

Four for a boy

Five for silver

Six for gold

And seven for a story that has to be told.

(Some people say ‘a secret never to be told’, perhaps you shouldn’t tell secrets, but you should tell stories!)

The golden eagle soared higher and higher towards the sun until he couldn’t lift another feather. Looking down on all the other birds beneath him, he called out that he was truly King of the Birds.

However he was in for a shock. Jenny Wren had been sharper than him and got one over him. She had taken tight hold of a feather under his great wing and hidden herself. As he started to tire, she flew out on top of his head calling out that she was above him.

The Magpie's Nest

The Magpie's Nest